Sycamore trees primarily belong to the genus Platanus within the family Platanaceae, a small group of flowering plants closely related to the Proteaceae family. The genus includes about 8-10 species, depending on classification, with notable members like Platanus occidentalis (American sycamore), Platanus orientalis (Oriental plane), and the hybrid Platanus × acerifolia (London plane).

These are deciduous angiosperms, meaning they produce flowers and shed leaves annually. However, the term “sycamore” can also apply to unrelated species in different regions, such as the sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus, family Sapindaceae) in Europe or the sycamore fig (Ficus sycomorus, family Moraceae) in Africa and the Middle East. For this discussion, we’ll focus on the Platanus genus, which defines the “true” sycamores botanically, characterized by their distinctive traits and evolutionary lineage dating back millions of years.

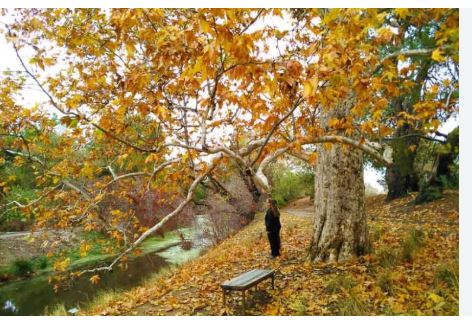

Sycamore trees are instantly recognizable by their mottled, exfoliating bark, which peels away in thin, irregular patches to reveal a patchwork of white, gray, tan, and green—a feature aiding identification in winter. Their leaves are broad, palmate, and lobed (typically 3-7 lobes), resembling maple leaves, with sizes ranging from 4-10 inches across, turning yellow to brown in fall. They produce small, inconspicuous flowers in spring, followed by spherical seed balls (achenes) that hang on long stalks, often persisting through winter and dispersing seeds via wind.

Sycamores are fast-growing, often reaching 70-100 feet tall (some exceeding 130 feet) with wide, spreading canopies up to 70 feet across. Their wood is hard but coarse-grained, and they’re prone to diseases like anthracnose, which causes leaf drop in wet springs, though hybrids like the London plane show greater resistance.

The native range of Platanus sycamores spans multiple continents, reflecting their adaptability. Platanus occidentalis thrives in eastern North America, from southern Canada to Texas, favoring moist floodplains and riverbanks. Platanus racemosa is native to California and Baja California, growing along streams in semi-arid regions, while Platanus mexicana and Platanus wrightii are found in Mexico and the U.S. Southwest. Platanus orientalis originates in southeastern Europe and western Asia, and Platanus kerrii grows in Southeast Asia’s tropical forests. The London plane, a cultivated hybrid, has no natural range but is widely planted globally.

Sycamores generally prefer temperate to subtropical climates with ample water, though some, like the Arizona sycamore, tolerate drier conditions once established. Their USDA hardiness zones vary: P. occidentalis spans Zones 4-9, P. racemosa Zones 7-10, and the London plane Zones 5-9, reflecting their climatic flexibility.

In landscaping their peeling bark and large, lobed leaves create a dramatic focal point, while their expansive canopies provide ample shade, making them ideal for parks, streets, and large yards. The London plane excels in urban settings due to its pollution tolerance and resistance to pests like the sycamore lace bug, often lining boulevards in cities like New York and London. American and California sycamores enhance naturalistic designs along waterways, though their aggressive roots and leaf litter require space and maintenance—best avoided near sidewalks or pipes. Ornamental cultivars, like variegated London plane varieties, add aesthetic variety, and their fast growth (2-3 feet per year) offers quick establishment, though pruning is needed to manage size and shape.

Their wood, though difficult to work due to interlocking grains, is valued for furniture, butcher blocks, and veneer—especially the London plane’s “lacewood” pattern. Historically, Native Americans hollowed American sycamore trunks into canoes, leveraging their massive size (some trunks reach 15 feet wide).

Ecologically, sycamores stabilize riverbanks, preventing erosion, and their hollows shelter wildlife like owls, bats, and bees. The seed balls feed birds, and fallen leaves enrich soil as they decompose. In culture, sycamores carry symbolism—P. orientalis is revered in Persian poetry, and Ficus sycomorus appears in biblical tales—while their longevity (up to 600 years for P. occidentalis) makes them living landmarks.

Whether providing shade along city streets, stabilizing riverbanks, or symbolizing cultural heritage, these trees captivate gardeners, ecologists, and historians alike.

Sycamore Trees

American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

The American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), also known as the buttonwood, is one of North America’s largest hardwood trees, native to eastern and central regions from Ontario to Florida and Texas. Growing 75–100 feet (23–30 meters) tall, with some exceeding 130 feet, it features a broad, open canopy and mottled bark that peels to reveal creamy white, gray, and brown patches. Its large, lobed leaves (4–10 inches wide) turn golden-yellow in fall, and single seed balls (1–1.5 inches) hang on stalks.

Thriving in USDA Zones 4–9, it prefers moist, alluvial soils along riverbanks and floodplains, tolerating floods and moderate drought. Ecologically, it stabilizes soils and shelters wildlife, while its wood is used for furniture and crates. Fun fact: Its hollow trunks once served as colonial shelters, and a massive specimen in Sunderland, Massachusetts, measures 115 feet tall. Ideal for large landscapes, it requires space and cleanup for shedding bark, making it a bold choice for parks or estates.

California Sycamore (Platanus racemosa)

The California Sycamore (Platanus racemosa), or Western Sycamore, is a Southwestern native, primarily found in California and Baja California, Mexico. Reaching 40–80 feet (12–24 meters) tall, it boasts a broad, irregular canopy with gnarled branches and mottled bark in white, gray, and tan hues. Its deeply lobed leaves (4–8 inches) are fuzzy underneath, turning golden to orange in fall, with seed balls in clusters of 2–7.

Thriving in USDA Zones 7–10, it grows in riparian zones with moist, sandy soils, tolerating floods and moderate drought. It stabilizes streambanks, supports wildlife, and is a stunning shade tree for native gardens, though its shedding requires maintenance. Its wood is used for furniture and pulp. Fun fact: Known as “Aliso” in Spanish, it names California landmarks like Aliso Creek, and its sculptural form inspired artists like Ansel Adams. Perfect for Mediterranean climates, it enhances xeriscapes and urban parks.

Mexican Sycamore (Platanus mexicana)

The Mexican Sycamore (Platanus mexicana), or Chino, is native to northeastern and central Mexico, extending to Guatemala. Growing 50–70 feet (15–21 meters) in cultivation, it can reach 100 feet in the wild, with a rounded canopy and mottled bark in creamy white and gray-green. Its lobed leaves (up to 8 inches) have silvery undersides, turning coppery-bronze in fall, with seed balls in pairs.

Thriving in USDA Zones 7–10, it prefers moist, well-drained soils in riparian zones, tolerating alkaline soils and drought once established. It prevents erosion, supports pollinators, and is a fast-growing shade tree for urban landscapes, with wood used for furniture. Fun fact: Its nickname “Chino” may stem from its exotic look, and it resists bacterial leaf scorch, unlike American Sycamore. Ideal for Texas and Florida, it offers quick shade in warm climates.

Arizona Sycamore (Platanus wrightii)

The Arizona Sycamore (Platanus wrightii), native to Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and northern Mexico, is a desert icon, growing 40–80 feet (12–24 meters) tall, with some reaching 100 feet. Its open canopy, mottled bark (white, gray, tan), and star-shaped, deeply lobed leaves (6–9 inches) turning bronze in fall distinguish it, with seed balls in clusters of 2–4.

Thriving in USDA Zones 7–9, it grows in desert riparian zones with sandy or gravelly soils, tolerating floods and extreme drought. It stabilizes canyon streambanks, shelters wildlife, and is a striking shade tree for xeriscapes, with wood used for crafts. Fun fact: Its star-shaped leaves earn it the nickname “star tree,” and Sycamore Canyon, Arizona, showcases its cathedral-like groves. Perfect for Southwestern native gardens, it requires minimal water once established.

London Plane Tree (Platanus × acerifolia)

The London Plane Tree (Platanus × acerifolia), a hybrid of P. occidentalis and P. orientalis, is a global urban staple, growing 65–100 feet (20–30 meters) tall with a broad, rounded canopy. Its mottled bark (creamy white, gray, olive-green) and lobed leaves (5–10 inches) turning yellow-brown in fall are iconic, with seed balls in pairs or triplets.

Thriving in USDA Zones 5–9, it tolerates pollution, compacted soils, and drought, ideal for city streets and parks. It mitigates air pollution, provides shade, and its wood is used for furniture. Fun fact: Called the “lungs of the city,” it survived WWII bombings in London, and a Manhattan specimen, “Big Daddy,” exceeds 100 feet. Perfect for urban landscapes, it requires maintenance for shedding bark.

Oriental Plane Tree (Platanus orientalis)

The Oriental Plane Tree (Platanus orientalis), or Chinar, native to the eastern Mediterranean and western Asia, grows 60–100 feet (18–30 meters) tall with a spreading canopy. Its mottled bark (white, gray, green) and deeply lobed leaves (5–8 inches) turning golden-orange in fall are striking, with seed balls in clusters of 3–6.

Thriving in USDA Zones 6–9, it prefers moist, well-drained riparian soils, tolerating floods and moderate drought. It stabilizes riverbanks, shelters wildlife, and is a cultural icon in Kashmir’s Mughal gardens, with wood used for crafts. Fun fact: A Greek specimen, reputedly planted by Hippocrates, may be 2,400 years old. Ideal for historic gardens or urban avenues, it adds timeless elegance.

Rzedowski’s Sycamore (Platanus rzedowskii)

Rzedowski’s Sycamore (Platanus rzedowskii), native to northeastern Mexico (Querétaro, San Luis Potosí), is a lesser-known species, growing 50–80 feet (15–24 meters) tall with a rounded canopy. Its mottled bark and lobed leaves (5–7 inches) resemble P. mexicana, but its seed balls are solitary or paired, with distinct leaf venation.

Thriving in USDA Zones 8–10, it grows in moist, riparian soils, tolerating floods and drought. It supports erosion control and wildlife, with potential as an ornamental shade tree, though its wood use is limited. Fun fact: Named after Mexican botanist Jerzy Rzedowski, it was distinguished from P. mexicana in 2009, highlighting its rarity. Suitable for warm, native gardens, it’s a conservation priority.

Gentry’s Sycamore (Platanus gentryi)

Gentry’s Sycamore (Platanus gentryi), native to northwestern Mexico (Sonora, Sinaloa), grows 30–50 feet (9–15 meters) tall with a compact canopy. Its mottled bark and lobed leaves (4–6 inches) are similar to P. wrightii, but its seed balls are smaller and clustered, with finer leaf lobes.

Thriving in USDA Zones 8–10, it prefers moist, rocky riparian soils in desert canyons, tolerating drought. It stabilizes soils and provides shade, with limited ornamental use due to its rarity. Fun fact: Named after botanist Howard Scott Gentry, it’s a desert specialist, thriving in harsh conditions. Ideal for Southwestern native plantings, it supports conservation efforts in arid regions.

Oaxaca Sycamore (Platanus oaxacana)

The Oaxaca Sycamore (Platanus oaxacana), native to southern Mexico (Oaxaca, Chiapas), grows 40–70 feet (12–21 meters) tall with a spreading canopy. Its mottled bark and lobed leaves (5–8 inches) resemble P. mexicana, but its seed balls are often solitary, with distinct leaf textures.

Thriving in USDA Zones 8–10, it grows in moist, riparian soils, tolerating floods and moderate drought. It supports erosion control and wildlife, with potential as an ornamental shade tree. Fun fact: Endemic to Mexico’s tropical highlands, it’s a biodiversity hotspot species, often overshadowed by P. mexicana. Suitable for warm, native gardens, it enhances riparian restoration projects.

Old World Sycamore (Platanus kerrii)

The Old World Sycamore (Platanus kerrii), unique for its evergreen foliage, is native to Southeast Asia, including southern China, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. Growing 30–60 feet (9–18 meters) tall, it features smooth, mottled bark (gray, green, brown) and elliptic, leathery leaves (3–6 inches) with entire margins, unlike lobed Platanus leaves, and small seed balls in clusters.

Thriving in USDA Zones 10–12, it prefers moist, well-drained soils in tropical rainforests, tolerating moderate flooding. It stabilizes riverbanks and provides shade, with potential as an ornamental in tropical gardens, though its wood use is limited. Fun fact: The only evergreen Platanus, its leaves resemble tropical trees, and some Vietnamese specimens exceed 200 years. Rare in cultivation, it suits frost-free, humid landscapes like southern Florida or Hawaii.

Guatemala Sycamore (Platanus lindeniana)

The Guatemala Sycamore (Platanus lindeniana), native to southern Mexico and Guatemala, grows 50–80 feet (15–24 meters) tall with a rounded canopy. Its mottled bark and lobed leaves (5–7 inches) are similar to P. mexicana, but its seed balls are paired, with unique leaf venation.

Thriving in USDA Zones 9–11, it prefers moist, tropical riparian soils, tolerating floods. It stabilizes soils, supports wildlife, and is a potential shade tree for tropical landscapes. Fun fact: Its name, “lindeniana,” reflects leaf similarities to linden trees, a rare trait among sycamores. Rare in cultivation, it suits humid, frost-free climates like Central America.

Himalayan Sycamore (Platanus × kashmiriana)

The Himalayan Sycamore (Platanus × kashmiriana), a hybrid of P. orientalis and possibly P. occidentalis, is prominent in Kashmir, growing 60–90 feet (18–27 meters) tall with a broad canopy. Its mottled bark and deeply lobed leaves (5–8 inches) mirror P. orientalis, with seed balls in clusters.

Thriving in USDA Zones 6–9, it prefers moist, well-drained soils, tolerating floods. It provides shade, stabilizes soils, and is a cultural icon in Kashmir’s gardens, with wood used for crafts. Fun fact: Its vibrant fall foliage, turning crimson, makes it a Chinar variant prized in Mughal landscapes. Ideal for temperate gardens, it adds historical charm.

Chinese Plane Tree (Platanus sinensis)

Found in eastern China, Platanus sinensis grows 60-90 feet tall with a straight trunk and peeling bark in shades of gray and white. Its leaves are deeply lobed, similar to P. orientalis, and its seed balls cluster in groups of 2-4. Thriving along rivers and in temperate forests, it’s a key species in Chinese landscapes, often planted for shade. Less known globally, it shares traits with the Oriental plane but is adapted to East Asian climates, with a history of use in traditional woodworking.

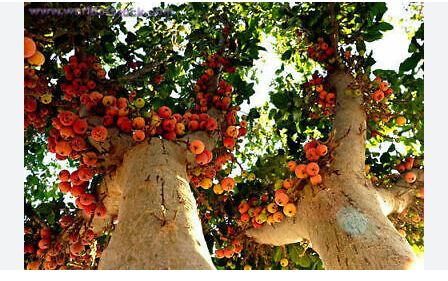

Sycamore Fig (Ficus sycomorus) Not a Platanus species

The sycamore fig, native to the Middle East and eastern Africa, is included due to its biblical “sycamore” name, though it’s a fig tree, not a Platanus. Growing 30-60 feet tall, it has rough, gray bark and heart-shaped leaves without lobes. It produces sweet, edible figs directly on its trunk and branches, a trait called cauliflory, and lacks the seed balls of true sycamores. Culturally significant in ancient Egypt and the Bible, it thrives in warm, dry climates and supports wildlife like birds and bats.

Cultivation and Care Tips for Sycamore Trees

Sycamores share common cultivation needs, thriving in full sun with well-drained, moist soils, though their specific requirements vary by species and climate. Most prefer USDA Zones 4–10, with tropical species like P. kerrii and P. lindeniana limited to Zones 9–12. Plant in spring or fall, spacing trees 30–80 feet apart to accommodate their large canopies, and water deeply during establishment (1–2 times weekly). Mulch with organic materials (2–4 inches) to conserve moisture, and fertilize young trees sparingly with balanced, slow-release fertilizers (e.g., 10-10-10). Prune in late winter to shape and remove damaged branches, minimizing cuts to prevent diseases like anthracnose, to which P. occidentalis is particularly susceptible. Monitor for pests like sycamore lace bugs and ensure good drainage to avoid root rot. Their rapid growth (1–5 feet per year) and lifespans (100–600 years) make them long-term investments for shade and ecology.

Ecological and Cultural Significance

Sycamores are ecological powerhouses, stabilizing soils, preventing erosion, and providing habitat for birds, mammals, and pollinators. Their canopies shade aquatic ecosystems, supporting fish, while urban species like P. × acerifolia mitigate pollution and cool cities. Culturally, sycamores hold deep meaning: P. orientalis is a symbol of eternity in Persian and Mughal traditions, while P. occidentalis marked colonial agreements like the Buttonwood Agreement of 1792. From Kashmir’s Chinar groves to London’s plane-lined streets, these trees weave history and nature, making them invaluable for restoration and heritage landscapes.

Choosing the Right Sycamore for Your Landscape

Selecting a sycamore depends on your climate, space, and purpose. For urban settings, P. × acerifolia excels due to its pollution tolerance (Zones 5–9). In arid regions, P. wrightii or P. mexicana (Zones 7–10) offer drought resilience. Tropical gardeners may opt for P. kerrii (Zones 10–12) for evergreen appeal. Temperate gardens suit P. orientalis or P. occidentalis (Zones 4–9) for historic or riparian charm. Consider mature size, shedding bark, and maintenance needs, as most sycamores are large and require cleanup. Source healthy specimens from reputable nurseries like FastGrowingTrees.com or Buchanan’s Native Plants for optimal establishment.