The California Sycamore (Platanus racemosa), also known as the Western Sycamore or Aliso, is a majestic deciduous tree native to the American Southwest, celebrated for its picturesque mottled bark, sprawling canopy, and ecological importance in riparian ecosystems. With its gnarled branches and vibrant autumn foliage, this tree is a cornerstone of California’s landscapes, providing shade, habitat, and cultural significance.

Its adaptability to Mediterranean climates makes it a favorite for urban and native plant gardens. In this detailed guide, we explore the botanical classification, origin, identifying characteristics, habitat, distribution, USDA hardiness zones, uses, and fascinating facts about the California Sycamore.

Botanical Classification, Origin and Native Area

The California Sycamore, scientifically named Platanus racemosa, belongs to the Platanaceae family, a small family of broadleaf trees primarily within the genus Platanus. The species name racemosa, meaning “clustered” in Latin, refers to the tree’s characteristic multiple seed balls hanging in groups, distinguishing it from the American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), which typically has single seed balls.

As an angiosperm, it produces flowers and seeds, with a monoecious reproductive system featuring separate male and female flowers on the same tree. Its taxonomic relatives include the London Plane (Platanus × acerifolia) and Arizona Sycamore (Platanus wrightii), with P. racemosa uniquely adapted to the arid Southwest. Hybridization with other Platanus species is rare in the wild, preserving its distinct traits.

The California Sycamore is native to the American Southwest, primarily California, with extensions into Baja California, Mexico. Its history dates back millions of years, with fossil evidence indicating Platanus species thrived across North America during the Miocene. Indigenous peoples, such as the Chumash and Tongva, valued the tree for its wood, used in tools and structures, and its shade for communal gatherings, with its Spanish name “Aliso” reflecting its prominence in early Californian culture. The tree’s preference for riparian zones along streams and canyons shaped its ecological role, supporting biodiversity in arid regions. Its cultural significance persists in place names like Los Alisos and Aliso Creek, tying it to California’s heritage.

Identifying Characteristics

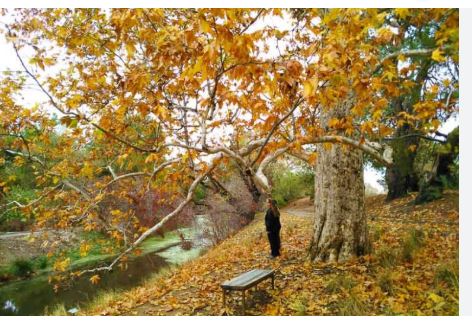

The California Sycamore is a medium to large deciduous tree, typically growing 40–80 feet (12–24 meters) tall, with some specimens reaching 100 feet (30 meters) and trunk diameters up to 6–10 feet. Its canopy is broad and irregular, often with gnarled, twisting branches creating a sculptural silhouette. The bark is a standout feature, peeling in patches to reveal a mottled mosaic of creamy white, gray, and tan, especially vibrant in winter.

Leaves are broad (4–8 inches wide), alternate, simple, and deeply lobed with 3–5 pointed lobes, fuzzy underneath, turning golden-yellow to orange in fall. The tree produces spherical seed balls (1–1.5 inches), typically in clusters of 2–7 on long stalks, dispersing fuzzy achenes in late winter. Its stout twigs and large, conical buds enhance its rugged charm.

Habitat

The California Sycamore thrives in riparian zones, including streambanks, canyons, floodplains, and seasonal washes, where it anchors moist, well-drained to poorly drained soils (pH 6.0–8.0), typically loamy or sandy. It is highly flood-tolerant, with roots adapted to periodic inundation, and requires full sun for optimal growth.

The tree often dominates in mixed stands with cottonwoods, willows, and oaks, contributing to streamside ecosystems by stabilizing banks, shading aquatic habitats, and supporting wildlife. In cultivation, it adapts to urban and suburban landscapes, parks, and native gardens, provided moisture is available, though it may struggle in compacted, arid, or heavily alkaline soils without irrigation.

Distribution

The California Sycamore is primarily distributed across California, from the Sacramento Valley south to San Diego County, with significant populations in the Coast Ranges, Sierra Nevada foothills, and Transverse Ranges. Its range extends into Baja California, Mexico, along coastal and inland drainages. Notable locations include the Santa Ana River, Ventura County’s Sespe Creek, and San Diego’s Mission Valley.

It has been planted extensively in urban areas, parks, and ranches throughout California and the Southwest for shade and ornamental purposes. The tree is not invasive but can naturalize in disturbed, moist sites. Its distribution is tied to water availability, making it a key species in California’s Mediterranean climate zones.

USDA Hardiness Zones

The California Sycamore thrives in USDA Hardiness Zones 7–10, tolerating minimum temperatures from 0°F to 30°F (-18°C to -1°C). It is well-suited to Mediterranean climates with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, though it can endure light frost. In Zone 7, young trees may require protection from severe cold, while in Zones 8–10, they flourish with minimal care. Its drought tolerance, once established, and flood resilience make it ideal for riparian restoration and urban landscaping in the Southwest, though it requires supplemental watering in arid conditions.

Uses

The California Sycamore is a versatile tree with ecological, ornamental, and cultural applications. Ecologically, it stabilizes streambanks, prevents erosion, and provides habitat for wildlife, including birds (e.g., hawks nesting in branches) and mammals (e.g., bats roosting in cavities). Its shade cools streams, benefiting aquatic species like trout.

In landscaping, its mottled bark, sculptural form, and colorful fall foliage make it a stunning shade tree for parks, campuses, or large yards, though its shedding bark and seed balls require maintenance in urban settings. The wood, lightweight and coarse-grained, is used for furniture, crates, and pulp, though less commonly than American Sycamore due to its smaller size.

Historically, it was crafted into tools and structures by Indigenous peoples. In urban environments, it mitigates stormwater, improves air quality, and offers cooling shade, enhancing sustainable designs. Culturally, it remains a symbol of California’s natural and historical legacy.

Fun Facts

The California Sycamore is brimming with captivating facts that highlight its unique character. Its mottled bark, peeling to reveal a patchwork of colors, earns it the nickname “ghost tree” for its eerie glow in moonlight. Some specimens live over 400 years, with gnarled trunks serving as natural sculptures in California’s canyons.

The tree’s seed balls, hanging in clusters, were used by children as playthings or woven into crafts by Indigenous communities. Its Spanish name, “Aliso,” appears in numerous California place names, reflecting its cultural prominence. The sycamore’s twisting branches inspired artists like Ansel Adams, who photographed its dramatic forms. It is less susceptible to anthracnose than American Sycamore, making it a hardier choice in wet springs. Finally, a famous California Sycamore in Santa Barbara’s Moreton Bay Fig grove is a local landmark, showcasing the species’ monumental beauty.

Cultivation of California Sycamore (Platanus racemosa)

Cultivating the California Sycamore (Platanus racemosa), a majestic deciduous tree native to the American Southwest, is a fulfilling endeavor for gardeners, landscapers, and conservationists aiming to enhance riparian zones, urban landscapes, or native plant gardens with a striking, shade-providing tree. Known for its mottled bark, sculptural form, and ecological value, this tree thrives in Mediterranean climates but requires careful management due to its size, shedding habits, and susceptibility to certain pests.

- Climate Suitability: California Sycamore thrives in USDA Hardiness Zones 7–10, tolerating minimum temperatures from 0°F to 30°F (-18°C to -1°C). It prefers Mediterranean climates with hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, similar to its California origins. In Zone 7, protect young trees from severe frost to prevent branch damage.

- Site Selection: Choose a spacious location with full sun, receiving at least 6–8 hours of direct sunlight daily, to support its broad, irregular canopy and vigorous growth. Ensure the site accommodates its mature size (40–80 feet tall, 30–50 feet wide) and avoid planting near buildings, sidewalks, or utilities due to its extensive roots and shedding bark.

- Soil Requirements: Plant in moist, well-drained to poorly drained soil with a pH of 6.0–8.0, preferably loamy or sandy, mimicking its riparian habitat. The tree tolerates clay and periodic flooding but thrives in fertile soils. Test soil drainage and amend with organic matter (e.g., compost) if needed to enhance fertility without compromising drainage.

- Planting Time: The optimal planting seasons are early spring or fall, allowing roots to establish before summer heat or winter cold. Dig a hole twice as wide and as deep as the root ball, positioning the root collar at or slightly above ground level. Backfill with native soil, tamp gently, and water deeply to settle the roots and eliminate air pockets.

- Watering Needs: Water young trees deeply (1–2 times weekly) for the first 1–2 years to establish a strong root system, keeping soil consistently moist but not waterlogged. Once established, the sycamore is flood-tolerant and moderately drought-tolerant, requiring supplemental watering during prolonged dry spells, especially in arid regions.

- Mulching: Apply a 2–4 inch layer of organic mulch (e.g., wood chips, bark) around the base, extending to the drip line but keeping it 2–4 inches from the trunk to prevent rot. Mulch conserves moisture, regulates soil temperature, and suppresses weeds, supporting young trees in urban or natural settings. Replenish mulch annually to maintain effectiveness.

- Fertilization: Fertilize young trees in early spring with a balanced, slow-release fertilizer (e.g., 10-10-10) to promote healthy growth, applying at half the recommended rate to avoid excessive foliage at the expense of root development. Mature trees rarely need fertilization in fertile riparian soils, as they are adapted to nutrient-rich environments.

- Pruning: Prune in late winter or early spring to remove dead, damaged, or crossing branches and to shape the canopy, using clean, sharp tools to prevent disease spread. Young trees may need structural pruning to encourage a strong framework. Minimize cuts to reduce susceptibility to fungal diseases like anthracnose, and avoid heavy pruning to maintain natural form.

- Pest and Disease Management: Monitor for pests like sycamore scale, lace bugs, or borers, treating infestations with insecticidal soap or neem oil. The tree is less prone to anthracnose than American Sycamore but may still develop leaf blight in wet springs; improve air circulation and remove infected debris to manage it. Ensure good drainage to prevent root diseases.

- Spacing: Space trees 30–50 feet apart to accommodate their mature canopy spread, ensuring adequate sunlight and air circulation to reduce disease risk. For riparian restoration or group plantings, plant 20–30 feet apart to mimic natural stands. Consider their height (up to 80 feet) when planning near structures or power lines.

- Wind Protection: Young sycamores, with shallow roots, are susceptible to windthrow in exposed areas. Stake newly planted trees for the first 1–2 years using flexible ties to allow slight trunk movement, which strengthens roots. Remove stakes once established to promote independent growth and prevent girdling.

- Winter Care: In Zone 7, protect young trees from winter damage by wrapping trunks with burlap to prevent frost cracks and mulching heavily around the base to insulate roots. Water adequately before freeze-up to prevent dehydration, as deciduous trees can lose moisture in winter. Mature trees are cold-hardy and require minimal winter care in Mediterranean climates.

- Long-Term Growth: California Sycamores grow moderately fast (1–2 feet per year), reaching 40–80 feet at maturity, with lifespans of 200–400 years in optimal conditions. Their mottled bark, colorful fall foliage, and ecological benefits make them ideal for shade, erosion control, or wildlife habitat. Regular monitoring for pests, diseases, and structural integrity ensures longevity in urban or natural landscapes.